Space Weather Monitors The

Space Weather Monitor Program • What

is a Space Weather Monitor? • How Does

the Sun affect the Earth? • Access to Data

Stanford's Solar

Center, in conjunction with the Electrical Engineering Department's

Very Low Frequency group and local educators, have developed inexpensive

space weather monitors that students can install and use at their local

high schools and universities. The monitors detect changes to the Earth’s

ionosphere caused by solar flares

and other disturbances. Students "buy in" to the project by building

their own antenna, a simple structure costing little and taking a few

hours to assemble. Data collection and analysis is handled by a local

PC, which need not be fast or elaborate. Stanford provides a centralized

data repository and blog site where students can exchange and discuss

data. Two versions of the monitor exist - one low-cost designed for

placement in high schools, nicknamed SID (Sudden

Ionospheric Disturbance), and a more sensitive, research-quality

monitor called AWESOME, for university

use. This document describes using data from the SID monitor. You need

not have access to a SID monitor to use the data.

A space weather monitor measures the effects on Earth of the Sun and solar flares by tracking changes in very low frequency (VLF) transmissions as they bounce off Earth’s ionosphere. The VLF radio waves are transmitted from submarine communication centers and can be picked up all over the Earth. The space weather monitors are essentially VLF radio receivers. Students track changes to the strength of the radio signals as they bounce off the ionosphere between the transmitter and their receiver.

How Does the Sun affect the Earth? The Sun affects the Earth through two mechanisms. The first is energy. The Sun spews out a constant stream of X-ray and extreme ultraviolet (EUV) radiation. In addition, whenever the Sun erupts with a flare, it produces sudden large amounts of X-rays and EUV energy. These X-ray and EUV waves travel at the speed of light, taking only 8 minutes to reach us here at Earth. The second manner

in which the Sun affects Earth is through the impact of matter

from the Sun.

Plasma, or matter in a state where electrons

wander freely among the nuclei of the atoms, can also be ejected from

the Sun during a solar disturbance. This “bundle of matter”

is called a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME).

CMEs flow from the Sun at a speed of over 2 two million kilometers per

hour. It takes about 72 hours for a CME to reach us from the Sun.

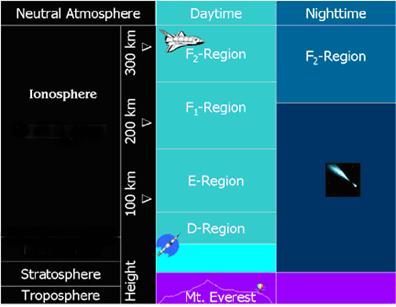

The Earth's Ionosphere The ionosphere has several layers created at different altitudes and made up of different densities of ionization. Each layer has its own properties, and the existence and number of layers change daily under the influence of the Sun. During the day, the ionosphere is heavily ionized by the Sun. During the night hours the cosmic rays dominate because there is no ionization caused by the Sun (which has set below the horizon). Thus there is a daily cycle associated with the ionizations. In addition to the daily fluctuations, activity on the Sun can cause dramatic sudden changes to the ionosphere. When energy from a solar flare or other disturbance reaches the Earth, the ionosphere becomes suddenly more ionized, thus changing the density and location of layers. Hence the term “Sudden Ionospheric Disturbance” (SID) to describe the changes we are monitoring. It is the free electrons in the ionosphere that have a strong influence on the propagation of radio signals. Radio frequencies of very long wavelength (very low frequency or “VLF”) “bounce” or reflect off these free electrons in the ionosphere thus, conveniently for us, allowing radio communication over the horizon and around our curved Earth. The strength of the received radio signal changes according to how much ionization has occurred and from which level of the ionosphere the VLF wave has “bounced.”

SID monitors are being placed around the world as part of the International Heliophysical Year. Data collected from these sites is stored in a centralized data server, hosted at Stanford, and accessible to all: http://sid.stanford.edu/database-browser/ To do the described activities, students may use their own SID data, if they have it, or use data from the central server. Hence students need not have their own monitor to receive and analyze real scientific data!

|